Every Birth is a Story

There is always a start. The first step. For everyone. Sometimes you take that step alone, entirely on your own volition, and leap, a fuzzy sparrow (such strong new wings you have) straight up, to the heavens. Sometimes you are dragged kicking and screaming—by the arm, by the hair? Sometimes you are shoved impatiently from behind, an outsized hand pressed against your back, your reluctant little feet stuttering nuhuh nuhuh beneath you. I want to say there is a fourth way—where someone else gently holds out their hand, and you take it. You both choose to walk together. It’s a good feeling, even if it’s walking just to the movies, even if it has nothing to do with starting a life. Synchrony. The state of not being alone. But I never had much experience with that. Least of all in the beginning.

Birth. The very first of first steps.

Up to the point of my birth(ejection/rejection), I (fetus/baby/smoke ring) had only known shy warmth and wiggle wet. Up to that point, I (fetus/baby/dustball) was care-less, time-less, thought-less. Then came the shove. The oomph, the ahhh (rude/reluctant/happy/mindless), the big bang. This specific act of creation, not of a universe, but of a life. Me. Also, the outsized hand in this case belonged to my mother, not god, or physics. My mother, with the mighty power of her mighty contractions pushed (painfully/ecstatically/fearfully) the fetus/baby/me into this new world with a tsunami of grunts and heaves and iiyiiyiis. I swam out. Into the new. Into the differentiated. I grew edges, became defined. More or less.

I would like to imagine, that at my moment of arrival a brass band, the golden horns pointed skyward WAH WAHHed the announcement. A bouquet of helium balloons spelled out H A P P Y. A stuffed animal—those friendly frozen smiles, those big eyes popping—parade. The grand marshal, complete with bow tie purple dachshund, barked a congratulations, you have now completed the very first step of first steps. Graduation/Separation/Activation Day. Electricity on. Water running. All the lights high-beamed illuminating the floppy soft-skulled swimmingly not-quite-muscled-up brand new me.

Though my new here was more probably lonely than bright. The signals announcing my entrance dialed down to just above mute. A ho hum can’t-wait-to-get-back-to-bed doctor. A distracted, if efficient, night nurse tying off the cord. And the other body in the room? My mother. Twilight sleeping. It was oh so long ago. In other words, a pucker-faced, bald-ish, wriggly (what a light-weight I must have been) wet-eyed me minnowed out into a colorless chill, a shock of close-your-eyes far too bright illumination. The handoff from indistinction to distinction was as unmemorable as a dull page turned. I don’t know when she first held me. The first moment of me separate from her. I suppose it was when she pushed away her own drawn-out drugged-out dreaming.

What was it, my birth, for my mother? The instigator, the pusher-outer. I don’t know much (if anything) how my mother felt. If she feared she would die if we stayed connected a minute longer. If she imagined me for nine long months a parasite, an invader, a tapeworm eating all her five-foot one inch up. If the pain of birth was her way back to freedom. If the separation, my own definition, that I am trying here to talk about was hers to re-gain, not mine to have. She never said. I don’t know if she was happy to see me.

All these things, I never asked.

Can a baby be overwhelmed by loss? Imprinted by loss? Forever longing for those before-memories they can never re-grasp? Those memories always hidden in the long just-before-sunrise-before-thought shadows: the mother-heartbeat-echo, the sloppy water-slosh, the dreamy translucence. Buried under layers of light-shock and muscle-startle and nothing even close to soft-as-water flesh. The whoosh of chilly air flooding naïve lungs, the uncompromising gravity scraping/deflating the fetus/baby pre-beginning. The before. The curled up, knees to face, hand to mouth, muffled, oh so quiet, my floating floating floating. My feather-light before.

But yet, adult me doesn’t look to the fish. I don’t look to diving into the heavy weight of the sea. It’s birds, so light, so unfettered, flying in their womb of air that move me.

***

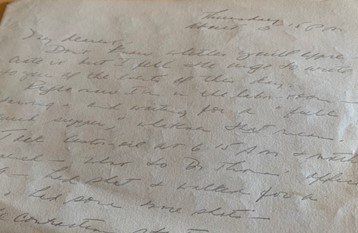

I sit at my dining room table with a letter, not a birth letter (not Dear Baby), but a day of my birth letter. Some evidence, to pick apart, sent to me by Joel, my brother, found in a pile of papers after my mother’s death. Some words, gray wisps of smoke on a yellowed page, that have now travelled to me from my before-I-knew-her mother. I am now so much older, so much more gray-haired, than she was when she wrote this.

Thursday, about 5 PM. Precisely penciled cursive heading. Written by my mother, who is not quite in labor, in the labor room of a Montgomery, Alabama hospital where I will soon arrive. The salutation, “My dearest,” not addressed to me. Not My dearest child, you will soon be entering into this world… I don’t exist yet apart from my mother. My mother hasn’t (doesn’t want to? can’t face it?) accepted my existence. I had not yet been required (it will happen soon, very soon) to take my first wormlike shudder into this world. My mother is focused on another, already happened, separation.

I was born in Montgomery, Alabama, late at night. My Aunt Gloria (my mother’s loud loud sister-in-law) and Grandmother (my father’s white-gloved mother) were in Montgomery, traveling from NYC and Birmingham, respectively, taking care of my two older already-entered-into-the-world brothers, Marshall, age two and Joel, age four. Marshall, I imagine, was thin and nervous. Joel, stolid and round. My father was not there. I was born in September, and he had left, weeks before, for Texas, to teach college in a small east Texas town. September would have still been hot. My mother in the labor room alone—I imagine her sweating—with a borrowed pencil and paper, writing my father (Dear Father/Dear Historian/Dear New Professor?) a letter.

My dearest. Did I ever hear that growing up? My father kissed the top of my mother’s head (he was a big, six foot, one inch heavy-boned man), a whole foot between them, on very rare occasions. I don’t remember her touching him. Not even fingers touching as she passed him plates of food.

My dearest…I felt the urge to write.

***

I am well into my twenties, and my parents have come to visit. A trip to the West Coast. I have not seen them in five years, a fact I do not think of as strange, nor bothersome. I knock on their hotel door. My mother opens (I also do not think of it as strange that my parents stay in a hotel rather than my apartment) and I see my father, stretched out on the hotel bed (as small as the room must have been, I see him from very far away) crying. Well, more than crying. He is wailing, he is gasping for air, mouth open, eyes scrunched closed. I breathe out confusion and startle. I have never seen him cry. My mother shakes her head. He’s depressed, she says. She turns back to him. Stop it, she says. I wonder, but don’t say, if he is sad because he has never come this far west. Because he is such a long way from home.

***

The day they leave, when I drive them to the train and turn to exit the station, my mother, face blank, sitting on the hard wood bench, looks up at me, I love you. Those words, (has she ever said them before?). I turn back. Oh, I squint, seeing a shape that hasn’t gathered enough form for me to name. I am wordless. Beyond the oh that has rolled off my tongue, a dark blank. Those words, the first and last time I ever hear them from her. Though she lives more than thirty more years.

***

My dearest…I felt the urge to write…

I am the third (and last) child, and, as it turns out, a much easier birth than my brothers. Joel had arrived into this world, full breach, buttocks first, and Marshall, weeks premature, came out, horrifyingly on his feet. What a way to almost break a leg. I, full-term, positioned correctly, head first (perhaps it was my own volition, this birth, perhaps my mother and I were, in this instance, walking hand-in-hand). Hooray.

I feel the urge to write to you of the events of this day.

This day. Which included, she writes, a morning plug of castor oil, injections (undefined) and a full liquid supper in the labor room.

My mother is writing a letter to my father because she is still in Alabama and he has left—the job calling for him in September—for Nacogdoches, Texas (what a swagger, though my father is more brooding than swagger, of a name).

This week with you away has been quite awful for me—guess I’m not cut out to be a pioneer wife independent woman after all.

I was, for a long time, such an easy child, my mother said repeatedly said to me, with her index finger circling towards me like a bird of prey. Quiet. Un-demanding.

I was born in Alabama where race, in this hospital that I imagine was white people only, was featured prominently on my birth certificate. I was born into a family of two brothers, a mother, and a father, and one terrier bird-killing dog. In photos, also grayed with time, my brothers, especially Marshall, who is two, seem especially curious about me. I was born into a family of professors and intellects. A Russian side (mother) and a father with links to the Daughters of the Revolution. I was the fifth time my mother was pregnant in four years. She had miscarried twice. I was not a miscarriage. I don’t know if she was ever pregnant again.

I do love you so.

I hope your first days of teaching go OK—I am sure they will—your mother and I agree that you’re the most wonderful son & husband & father there is—so why not a most wonderful teacher—I really think you will be

She missed him, I suppose.

Six weeks later, she would travel, alone, by train from Alabama to rural Texas, with new-born me, and two small children. A pioneer wife whether she chose to be or not.

***

For years, Joel and I (I don’t know about Marshall) would proudly proclaim that our parents loved each other more than they love their children. We were proud. Of their Independence. From us. I wanted so much to be (a mother?) like my mother.

***

My mother, always for me, in the present tense:

I am twenty-eight. She sits on a chair across from me watching me nurse my child on the couch. Her look is greedy, fascinated. She tells me again the story of how she could not nurse. It didn’t work. She tried twice. No milk. Marshall, premature, was failure to thrive. With me, she did not try.

Is it the tone? Is it the hands on her hips? Is it the smile that doesn’t match her eyes? Is it that she turns away from me, and repeatedly says to the wall, “That’s what they say, it’s important to bond.” Is it the ha ha that she forces out afterwards?

***

I am three, sitting in dry dusty dirt under a tree. Acorns and oak leaves scatter messages around me. I etch lines in the dirt with a broken stick, singing La, la, la.

***

I am four. My mother has gone back to work, to teach her first class at the same college my father teaches. She has left me in this strange house. I sit in the strange back yard, crying. I refuse the offered plate of cookies. Stomach tight, I cannot eat. My mother comes back whenever she comes back. I see her looking out at the yard at me, a blur through the screen door of the strange house. I freeze. Her hands on her hips. Her lips twitch. I cry louder; it can’t be stopped.

***

I am five. My father is gasping out air. Deep huge gasps behind a door—their bedroom—I am not allowed to open. I don’t know what is happening and I cry, shoulders shaking, along with each gasp. I don’t know what these loud moans mean. Marshall gives me the words years later. Asthma attack. How it’s not the inability to breathe in, but the inability to push out your breath that can kill you.

***

I am six, and it is snowing in Mississippi for the first time in fifty years. My mother hands me the largest spoon ever, her one and only batter mixing silver spoon, to go out and eat from the half-a-foot (!) piles of snow.

How delicious it is to be numb.

***

I am seven. A mother-daughter trip in our percale handmade dresses, two hours on a Greyhound bus, watching the pine and cotton fly by, to the big city. Birmingham! The city with more-than-one-story buildings. Escalators! I am allowed to jump on my first escalator. Up and down. And up. Oh, young heart. This time, it takes no effort to fly away.

***

A ring of evergreen yew-like bushes. A ring of scratchy bushes to crawl into. The inner circle of dirt a contrast to the heavy unending green. A ring of bushes to crawl into where I can sit in a circle of shadows (protected) and watch the luminous treacherous outside—feet, legs, hands, walking by. No one ever sees the inside. The slipping into the shadows—wall, bush, bed—is my secret power.

***

Outside the dining room, through our curtainless windows, letter still in my hand, I look for the song bird’s spring fledglings. Pushed (or left) from the nest, they hobble around weakly cheeping after their mothers. Feed me, feed me. And the bird-mothers do. For a time.

***

When I started, as an adult, some-would-say-long-overdue therapy, my mother was alive. When I quit, some-would-say-finally-enough-is-enough, she was years dead. This was not even at the beginning of it:

Leaning towards me, my therapist said, “It’s possible to have a relationship without feeling desperate.” Sometimes, arms like a straitjacket around my chest, I answered, “I’m tired. I’m tired of the effort it takes to hold myself to the ground.”

I stuttered, my body slumped, the room flickered in and out, “All my life I have been afraid.” He looked right at me. Not at any of the four walls that he could have.

This is my struggle. For me to say “I” instead of “you”, as in “I couldn’t stand it” instead of “You couldn’t stand it.” “My” in place of “the”, as in “my body” instead of “the body”. As in “my struggle” instead of “the struggle.” Reader, am I inviting you in? Or pushing myself out? Is it possible to walk hand-in-hand?

***

It’s not often, but here she is. My dead mother invading my dreams. We are together, traveling, visiting a city, wandering in a park. We are traveling in the way we used to travel, with our rhythm of food, books, her talk of this and that. I tell her that I am going to try a different way today, through an adobe maze of twists and turns. I will meet her back in the park. I get lost, of course. I ask more and more people where to go, but the directions confuse me. I lie on top a sandy hill, my palms smoothing the rough grains, the dips and ridges, as the time tick-tocks, and look at the clouds and wonder why I don’t move. And wonder why (this is the important part) I don’t want to move. I do not want to try to go back.

***

Every story has an ending. This one could be me becoming a parent at age twenty-eight. When becoming a parent became more important than being a child. It could be me, when I am standing over Alex and Zack, in the living room of a tiny apartment, newborns swaddled in flannel, duo white garage-sale bassinets, my hands warming in the gentle rise of their sleepy breath. It could be me, feeling, for the first time in my life, that aching let-no-harm-come-to-you need to protect. But it isn’t.

***

Let’s say it’s two years later, and it happens as suddenly as the final moment of birth, where you go from not-parent to always-and-irrevocably parent. It comes without warning, or, at least, no warning that I recognize. No letter arrives that informs me “If you do not respond in 10 days, the lights will shut off, the water will stop flowing.” No forecast that alerts me the weather will shift, get down off the mountain, there’s an otherworldly storm that will blow you away, no ocean recedes by thousands of feet from shore to give me at least some minutes to run to higher ground. It’s here. Tsunami. Snowstorm. Flood. In the brightness of day, I protect myself with Cherrios and halved-grapes and cloth diapers and The Little Engine that Could, read it again!, and homemade Play-Doh and swing sets push me, Mommy!, and bath-time. But there is no shield at night.

Two weeks of this. I fall asleep. Yes, I do. I sleep until I am 3 A.M-awake again and something pulls at me. Not Alex and Zack, who are long past their own midnight wakings, who are curled in their beds toss turn suck thumb across the hall, exhausted from their toddler playing. Not Mike snore sigh twitch dreaming his own Fibonacci grad school pure logic dreams beside me. Not this real and sturdy life.

3 A.M., I am alone except for my nightstand clock, little monster, its full and disapproving face, beside the bed, tapping on my shoulder.

Clock: 3:01, 02…4:05, 06.

Me: What do you want with me?

Clock: 4:07…

Is it possible to escape? Is it possible to get up, take the twenty steps needed down the hallway to the kitchen, to that place of all sustenance? I count them now like I had been counting time. Twenty steps to untether myself from time. What I didn’t know, was that time, that clock, that mumbling barb-wired devil of a god, was the only material thing that had been holding me to the ground.

Did you know that dark can come alive? Dark can be the one shoving you along. Dark can speak to you in a voice as loud as anything you have ever heard—louder than a woman’s deep ooooph labor-moaning, louder than the babies thin wahh of early waking, louder than the bam-belt-smack-cries of a childhood, louder than a beating heart. In this jet-engine-dark, flash flood, tornado dark, in this kitchen where I stand leaning against the counter, without a clock to watch, dark is the only thing I know. Dark denies me any separation, dissolves the lines.

I crumble into the hands of the dark.

***

Things happen during those new-parent, want-to-be-a-better-than( a perfect) -my-parents, years. Things that can’t always be measured. I made myself gone, had agreed with myself that it was important to not resist, to let myself be eaten up. No force, no threat. No you have to. No blame someone else. I wanted to bang the drums loudly, to spell out only H A P P Y. Happy to be with you, my children, happy to be not-me-only-you. Happy to be not-my-mother. Those steps, towards my slippage into the dark, were made entirely of my own volition.

***

A simple pine block of knives on the counter in the kitchen, a wedding present from the very same Aunt Gloria who was at my not so heralded birth. The knives, a reason, maybe, to be in the kitchen and not curled on the couch. Knives, a might be a scrub-the-floor-clean solution. It’s true. I thought about it. I thought about what it would be like to take that (first?) (last?) step.

***

Synchrony. It does exist. Sometimes two bodies come together. Sometimes two people walk at equal paces. Can I call it love?

Mike, husband, father, had turned in bed. Found emptiness instead of a body, found a blank that he knew should be filled. Half asleep, he had followed my crumbs. Standing in the kitchen, soft with caution, he glowed, if only a dim flicker, into my darkness. He was so near.

“I can’t see myself.”

“I’m lost.”

“Find me.”

He reached out, like the surest ripple of water.

***

Sound escapes, cries out, sometimes without volition, is invisible, can sometimes be music, sometimes be vital, cannot be caged.

If I could turn my body

into sound my hair, wind

chimes at dawn my mouth,

pebble beach clatter

my eyes, a camera click

my hands, sparrow

twitter, a fog horn belly

a wing whirr heart

tick-tock

arms, crunch stick hips

whistling marmot legs

my feet—a river,

snow melt, boiling

over rocks.

***

It’s a fact. A mute baby does not get fed.

Also a fact. Bodies can turn into sound.

Abby Howell

Abby Howell has an MFA in poetry from Warren Wilson College. Her work has been published in numerous journals including The North American Review, Willow Springs, New Letters, and Dorothy Parkers Ashes. She is currently working on a series of short lyric essays about her childhood in Mississippi. She now lives in the Northwest.