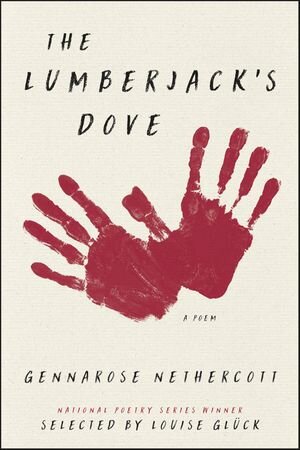

Infinite Stories & The Lumberjack's Dove

The Lumberjack’s Dove by GennaRose Nethercott

GennaRose Nethercott is the author of The Lumberjack’s Dove (Ecco/HarperCollins, 2018), selected by Louise Glück as a winner of the National Poetry Series. Her other recent projects include the narrative song collection Modern Ballads, and Lianna Fled the Cranberry Bog: A Story in Cootie Catchers (Ninepin Press 2019). Her work has appeared in BOMB Magazine, The Massachusetts Review, The Offing, PANK, and elsewhere, and she has been a writer-in-residence at the Vermont Studio Center, Art Farm Nebraska, and the Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris. She is currently a Massachusetts Cultural Council Artist Fellow.

P.S. You can read GennaRose’s work in TIMBER here.

A teammate from high school dies unexpectedly. Motorcycle accident, say. Someone else—a parent or grandparent—leaves this world after months or years in a hospital gown. The person you think you’ll marry calls from 2,000 miles away to say it’s over and that when the timer they’ve set for 10 minutes goes off, this phone call will be, too.

So often in this life, the event behind an aching, persistent grief fits into the space of a sentence. Both the noun and the verb at hand are simple, familiar even, and easily comprehended. What they represent in this exact pairing becomes anything but. The story, when we tell and retell it, feels far too small to leave so much of who we are or thought we were ablaze in its wake. In this way, the language of loss is necessarily reductive—at best, it’s shorthand for an emotional experience that doesn’t translate and can’t be shared. It’s partially this conflict between the simplicity of talking about loss and the complexity of experiencing it, I think, that keeps us coming back to Elizabeth Bishop’s “One Art.” By repeating that famously nonchalant line, “The art of losing isn’t hard to master,” in increasingly dire circumstances, the villanelle replicates some of grief’s reprocessing work after the facts of loss have settled.

GennaRose Nethercott’s The Lumberjack’s Dove achieves a similar effect in a much longer, more magical, decidedly postmodern form. It presents a concise narrative whose major plot points fit into the book’s opening paragraph:

It’s the same old story:

A lumberjack loses a hand to his own axe. The hand becomes a dove. The hand tries to fly away but the lumberjack catches it beneath his shoe. You know this story. The lumberjack ties one end of a string to the hand & the other end to his belt. Then the lumberjack walks out of the forest, the airborne hand fluttering along right behind. (3)

The complexity comes not from this narrative in its own right but from its circuitous retelling across six sections of prose blocks. Like grief itself, this story breathes, grows and shrinks, folds inward, and recalibrates—but never quite resolves. The voice of a self-aware narrator, who borrows an ethos of timeless wisdom from the world of fable and folktale, interjects often to remind us that the particulars here matter less than their synthesis: “Remember, there are infinite stories about separation. By infinite stories, that is to say that there is this story, & only this story, told many different ways” (14).

Like Bishop’s speaker in “One Art,” Lumberjack’s struggle comes to us, for the most part, in a deceivingly matter-of-fact voice. On the one hand, that initial declaration that “It’s the same old story” (3) feels tongue-in-cheek. Sure, we’ve experienced loss, but we certainly haven’t chopped our dominant hands off and watched them turn into actual doves. But we do know this story, to the degree that Lumberjack’s inability to comprehend his situation is human. He suffers a fantastical loss, but its fantastical aspects are not what keep him from comprehending it. Instead, he “knows little of what doctors can & cannot do. He knows little of the rules of removal & replacement” (15). Through this, the poem maintains a balance between a kind of figurative language—one that is always aware that it points outward from the story world—and an immersive magical-realist experience.

Nethercott manages this sleight-of-hand (apologies for the pun) between the magical and the painfully real in part by working with short, syntactically straightforward sentences. What’s more, many of these sentences make masterful use of the passive voice, which in this context reads nothing at all like the Comp 101 faux pas it’s often made out to be. Take, for example, this passage from the beginning of Part III:

Like all major U.S. highways, I-91 functions as a direct trail to the witch doctor. All you have to do is drive straight. You can tell you are near when the radio static is replaced with birdcalls. (21)

If we get rid of the passive verb and birdcalls simply replace radio static, we’re left with a one-off event whose occurrence can be pinpointed in time. To be replaced instead establishes a new permanence, a sustained state of being. Again, this is how loss works: it not only happens, but afterward continually is. The passive voice’s emptiness, which we might otherwise bemoan, actually acts assertively here. It also underscores the nonchalance with which elements like the witchdoctor or the hand’s transformation permeate the story. The simplest and most direct verb for existence works to linguistically preempt skepticism.

With a nod to choose-your-own-adventure serials, the end of the first section introduces a split in the plotline: “Lumberjack drives towards the witch doctor or he drives to the E.R. depending on who’s telling the story, & depending on if the storyteller is a liar” (8). Unlike Goosebumps, though, this poem requires us to read both options with an understanding that each “version” of the story can—indeed, must—exist as legitimately as the other, and at the same time. The narrator insists as much when Lumberjack approaches the witch doctor in Part III: “Sometimes, a story doesn’t make sense. Sometimes it will contradict itself, but be true, anyway” (28). The book’s penchant for this kind of multiplicity, suspending disparate events next to and within each other, means we get a mature and nuanced look at grief and the way emotions and experiences that might at first glance seem mutually exclusive can in fact live indefinitely at odds within us.

Not everyone who loves poetry loves prose poetry or feels enticed by the idea of a book-length prose poem. For the most part, I fall into this category of perhaps-closed-minded lovers of the traditional lyric. I say often that I’m looking for poems that make my stomach feel the way it feels when I crest a hill a little too fast in my car. I love when the sustained motion of a line, phrase, or stanza lets me get a little too comfortable, makes me marvel at its beauty or even laugh out loud, before hitting me with the shift in image or meaning it’s been building toward. Those moments don’t necessarily undermine the pleasure that precedes them, but they do force its reprocessing or recontextualization. At the line level, The Lumberjack’s Doveexecutes this move with devastating precision. Skillful shifts in the way this poem sees or processes an image happen in nearly every prose block, and for this reason I’d argue that most any lover of poetry, regardless of their preferred style, will enjoy the book. I’ll leave you with just one of those moments:

Simple tasks spring leaks when your grip is winged. A bottle shatters in its journey to the mouth. Handwriting adopts wide swoops as if caught on a thermal. It becomes impossible to trace the map of a darling’s skin, or dial the telephone, or hold a soupspoon. Instead, your hand will preen by the open window. Lift out of reach. Abandon the duties for which it was built. (17)

Mike Ranellone is a poet from New York. He holds an MFA from the University of Colorado-Boulder.