"Reaching Across Genres": Kristina Ten's Tell Me Yours, I'll Tell You Mine

Interview w/ Kristina Ten on her debut collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine

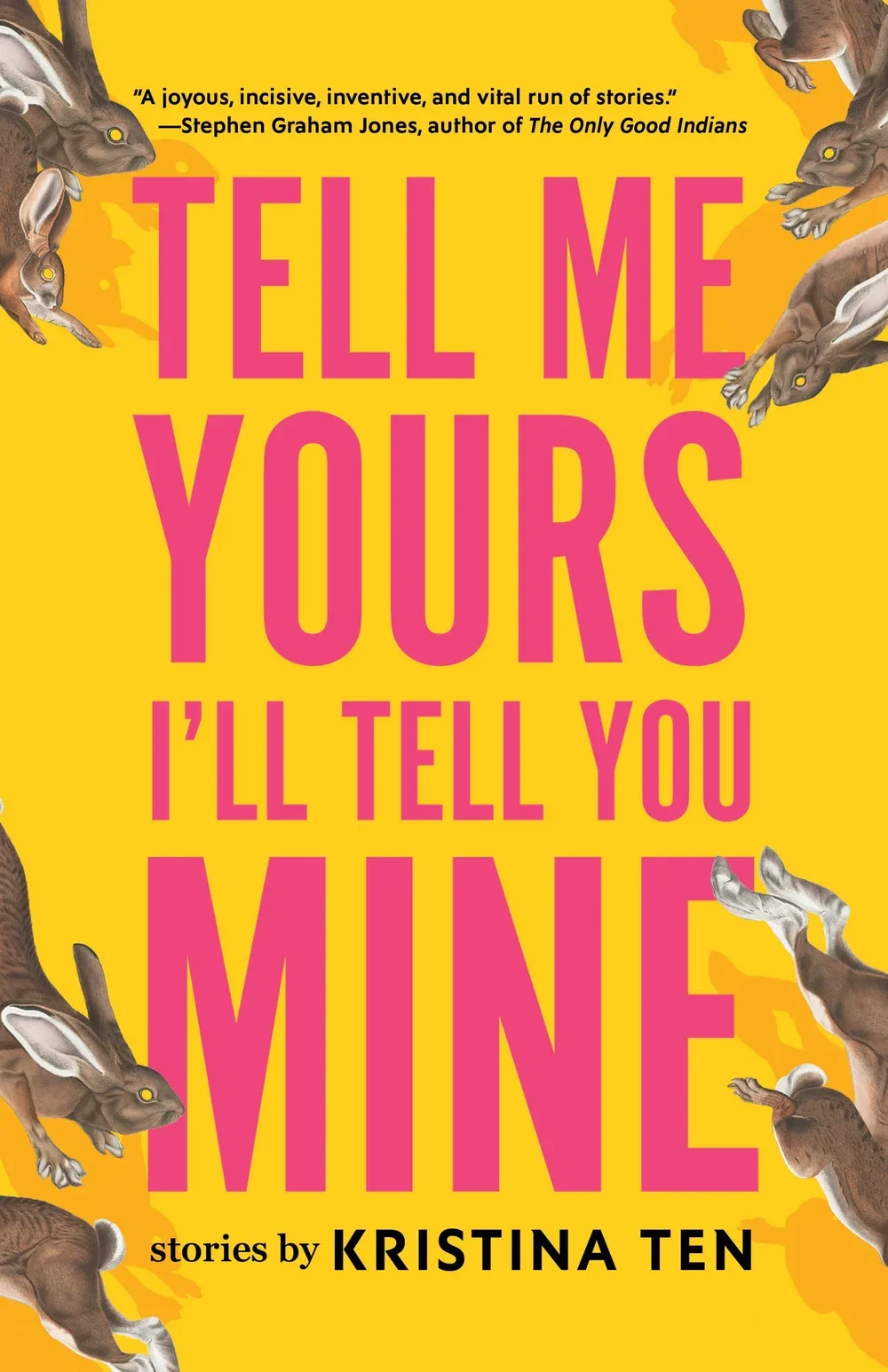

Kristina Ten is the author of Tell Me Yours, I'll Tell You Mine (2025, Stillhouse Press). Her stories appear in McSweeney's, The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy, We're Here: The Best Queer Speculative Fiction, The Best Weird Fiction of the Year, Gulf Coast, Passages North, and elsewhere. She has won the Stephen Dixon Award for Short Fiction, the Subjective Chaos Kind of Award, and the F(r)iction Writing Contest, and has been a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award, the Locus Award, and the WSFA Small Press Award. Ten is a graduate of Clarion West Writers Workshop and the University of Colorado Boulder's MFA program in fiction, and has received fellowships from the Ragdale Foundation and the Martha's Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing. Find her at kristinaten.com.

Kristina Ten’s debut story collection, Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine, takes us into familiar spaces—the school locker room, office, a “modest apartment on the north side of town”—only to split the earth beneath our feet, swallowing expectations and demanding our attention entirely. From ghost-filled halls to passengers with futuristic body modifications on an airbus through space, Ten’s twelve genre-crossing stories probe the horrors that oppressed bodies often experience without losing spark.

“The Curing” takes us through the snotty corners of a middle school where cliques alienate children who speak “the same funny‑accented English,” catapulting them into a seemingly innocent craft that turns all-consuming and supernatural. Conversely, “Approved Methods of Love Divination in the First-Rate City of Dushagorod” playfully describes a post-war city that’s developed three quirky “love divination methods.” Each piece will have you questioning whether you are really you, if your seemingly kind neighbor’s hiding a creature in his house, and that girl who never returned home from summer camp? Sure, watching your bloodstained underwear fly at the top of the flagpole is mortifying, but at Colden Hills Music Camp, real danger stalks the grounds.

Ten’s work reaches across genres—horror, sci-fi, magical realism, fantasy—entering unexpected and exciting worlds that often merge the extraordinary into ordinary realms while sharing surreal twists similar to The Twilight Zone. This unsettling collection will keep you wrapped in your sleeping bag, sometimes smiling, sometimes aching, but always entranced and eager to flip until the very end. And when it comes, you’ll glance around, realizing you’re the last one awake.

Congratulations on your first full-length publication! I’m genuinely in awe of the entire collection. It’s a banger, for sure. To start: what was the average day like in Kristina Ten’s head during the creation process? You can answer that, of course, however you’d like.

Thanks so much. Means a lot. The process has turned out to be different every time, because my life around it has looked different. I wrote Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine during grad school, so I was sneaking pages whenever and wherever I could, between the courses I was taking and those I was teaching. Lots of scarfing down cheese sandwiches on the thirty-minute speed-walk to campus. Lots of hiding from grading deadlines in the library stacks. Felt like I always had a hundred tabs open. It was a hectic time, but also really generative and exciting. The air was thick with creativity, ideas swirling from all directions. It was a lesson in grabbing your pen or keyboard and getting the words down whenever, since none of us could wait till we had a solid two-hour block to write—that luxury would never come. The best part is I didn’t have time to second-guess myself, either.

If I’m in the middle of a project, I’m writing more or less all the time. Even when I’m not in front of the computer—and especially when I’m showering or driving or a split-second away from falling asleep—some essential kernel of information will come to me. If I don’t have my phone on me, I might ask my partner to text me whatever it is I’m wanting to remember. So if you scroll through our texts, it’s normal stuff and then the occasional horrifying, contextless note like, “blood sacrifice from middle child??” or “look into degloving!”

Each story is unique yet there’s a few connecting strands—immigration, assimilation, sexism, longing for human connection—that weave throughout the book and ultimately tie the collection into one cohesive, important text. How do you balance the ordinary with the extraordinary while maintaining emotional resonance for your readers?

I don’t think much about the balance. For me, the magical and mundane have always existed side by side, and this coexistence feels like the most natural thing. People talk about realist fiction and speculative fiction as if they’re on opposite ends of a spectrum, but I’ve never understood that. With everything I write, I’m making an honest attempt to figure something out, or I’m trying to explain—sometimes to myself—what something really, truly feels like. The speculative and surreal stories I write feel, at least to me, like the most accurate, precise expressions of what I’m trying to get at. Realer than if I attempted to say the same thing using strictly realist stories, which would feel incomplete or inhibited somehow.

One reason for my easy acceptance of the supernatural in the everyday is that I grew up reading fantasy and fairy tales (shoutouts to Alexander Afanasyev and Diana Wynne Jones, among others). Another reason is, being born in one country and raised in another, I’ve always felt between, and of, two worlds—a person with an identity split (or better: doubled) across multiple axes. So I was always open to the idea of malleable and moving borders. In terms of the connecting strands you mention, those are difficult topics, and speculative fiction can be useful when dealing with difficult topics in that it allows for distance and defamiliarization. For instance, “The Advocate” is a story about medical gender bias, a topic that’s painful to write about and to read about. By also making it a story about a knight training for a jousting tournament, I’m exploring whether I can make that topic more…tolerable, maybe? And also whether looking at that topic from a new angle might shake something loose.

“Another Round Again” is incredibly weird. I love it. Can I ask what prompted your idea for that twist?

Nathan Ballingrud’s “The Visible Filth” was a big influence: the grimy atmosphere, the revelation of the strange, the protagonist’s gradual unraveling. “Another Round Again” was the last story I wrote for the collection. I’d just finished a couple allegorical works, and wanted to challenge myself to write something less tidy and more psychological. To present a broken character with a high level of empathy, which Ballingrud does so well. In “The Visible Filth,” Will is an empty person, a “nothing” person. I’m interested in what the lack of a strong sense of self can do to someone. It’s a more slippery horror to paint than, say, an evil clown or a haunted doll—these familiar, external, tangible things. How do you convey the horror of a vast internal emptiness, of being so personally unanchored that you could be swept away by the slightest current? It’s a horror of negative space, and what undesirable forces might fill it.

Another influence was Carmen Maria Machado, who spoke at AWP in Seattle about representations of queerness in literature. I’m heavily paraphrasing here, but the gist was that, if we’re consistently putting queer characters on a pedestal—they’re always kind, always virtuous, always likeable—what is that accomplishing, really? This holds queer characters to an impossible standard, burdening them with the responsibility of representation so they have to stay on their best behavior while never actually getting to be real people. Instead, queer characters should get to be as messy, flawed, contradictory, and therefore human as everybody else. That’s what I wanted Zasha to be. Not easy to categorize. Not easy to like.

You worked with Stephen Graham Jones, who I’m a huge fan of. What was that like for you? Is there a memory—something he taught you maybe or a funny moment in workshop—that’s stuck with you?

So much, really. May everyone get to have such a generous, disciplined, inquisitive, humble, and encouraging mentor. How he manages to put out the books he does while reading constantly and widely, and devoting so much time to his students and fans, I’ll never understand. That’s been as much an inspiration to me as questions of craft: the example he sets for living a writer’s life, and creating with a sense of urgency. Everything I know about autofiction I learned in his class on found-footage fiction, and by chasing curiosities born of it. You can tell he’s learning alongside his students, and that really changes the tenor of the class.

He once sent me a short film that might not be online anymore, or at least I can’t find it. It’s maybe ten minutes long and still one of the scariest things I’ve ever seen. The essence of it is there’s this couple: the guy is an incorrigible jokester, and the girl is telling him he always takes things a step too far. And in the end, that’s exactly what happens. You think the horror’s over and you’re on the other side of it, shaken but safe—but no, not yet, and so: maybe not ever. It taught me about turning that screw just one more time.

As for a funny moment? I once wrote a story about a samovar and turned out most people in the workshop had no clue what a samovar was. They’re a totally regular thing for me, because of my upbringing, but pretty hard to explain to someone who’s never seen one. Then maybe a year later Stephen emailed me a screenshot from… I think it was The Hunt for Red October?... and there was a tiny, blurry samovar in the background of the scene. And I was like, yeah!

What project[s] are you working on now (or looking forward to working on in the future)?

Right now I’m writing a number of essays related to Tell Me Yours, I’ll Tell You Mine: about the dangers of nostalgia, the creepy folklore of children, the allure of Y2K, the songs that inspired the book, and the great Mariana Enriquez. [Editor's note: Said essays can now be found at the included links.]

Off-topic questions: What part of the world do you want to explore next, and why? What silly, lovable quirks do your dogs have? What do you enjoy doing, besides writing? What kind of snacks are you eating to fuel that luscious, otherworldly brain of yours?

I’ve wanted to do a combo Portugal-Morocco trip for ages, and am also dying to visit Hong Kong, Scandinavia, and Alaska. If I could be traveling all the time, I would. Just want new-to-me stuff to be hitting my eyeballs round the clock.

Like most dogs, mine are made up entirely of lovable quirks. The older one likes to rescue stones from riverbeds. He’ll survey them all methodically, then carefully extract just the one that most needs his help before carrying it to the bank. Meanwhile, the younger one, who’s a golden retriever and supposed to love water, cannot swim. We have this handwoven kilim rug from Tbilisi that I try not to let the dogs sleep on because it can’t be vacuumed like regular rugs, and they’ve both learned to lay parallel to it, an inch from the edge, with just one paw crossing the boundary.

When I’m not writing, I’m reading, hiking, going to live shows (music, burlesque, puppetry, galleries), kayaking in the summer, snowshoeing in the winter, trying to find something to do with my hands (ceramics, papermaking, weaving, embroidery), thrifting, and…walking around. I could spend all day walking through a city, just letting the sound hit me. Or walking through a desert, and swap sound for silence.

I don’t snack very much, or I’ll eat my snacks during mealtimes and call it breakfast, lunch, or dinner. I’m a three-square-meals person. Unless I’m at the movies, where I’ll always get an ICEE. All the flavors, layer-caked together, except for green apple.

Havilah Barnett is a writer and strange-little-creature maker with poetry published in The Boiler, Pinch Journal, Collateral Journal, and others. With a background in emergency medicine (civilian and military), Havilah’s work often explores trauma, mental illness, and the effects of mutism in a deafening world. She’s been Assistant Editor for Pleiades Magazine, Editorial Intern for Boulevard Magazine, and is currently editor for Timber Talks. If Havilah’s ever missing she’s fondling animals in the dirt or has fallen off a cliff with her bike.